Our sailboat (Jeanneau 43DS) has been lithium powered for 10 months now – with a full 6 month cruising season in BC and Alaska mostly off grid (at anchor). It’s been a game changer not having to worry anymore about running out of power or shortening the life of the batteries by running them down to 20% or 10%.

Lithium batteries are a big subject that I can’t address fully here, so definitely read up elsewhere to learn! This post is just to share our particular setup, since we’ve had a few people ask. I’m not an expert or an ABYC electrician, but I have read marine electrical books, ABYC guidelines, numerous online sites, and have marine electrical experience on previous DIY projects.

It’s not necessary to do everything we did just to get lithium batteries. My goal here was a ground-up complete modernization of our boat’s electrical system. Since this was a new-to-us boat and many of the electrical components were old, this made sense. Many owners replace only one part at a time (ex, batteries, shore charger, etc) but then you get a mish-mash of old and new systems.

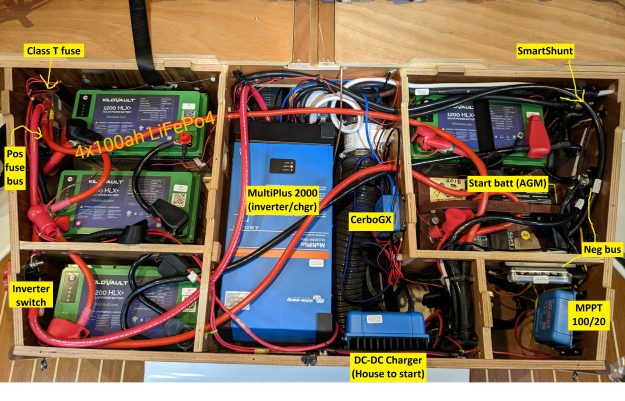

The “heart” of our system is under the aft berth. It’s a tight space to work in, and there were a few other options, but for a few reasons I packed much of it into here.