It’s winter, and for us that means it’s project season. Nearing 3 years of too many projects to count (but also a lot of sailing), I’ve been asking myself – did we actually end up with a project boat? While shopping for a boat, the one thing I was sure of was we didn’t want a project boat!

I had heard of people buying project boats and spending years working on them without sailing. I have a lot of admiration for people who do that, but for us sailing and cruising was always the number 1 goal. If a project boat meant we couldn’t cruise, we’d be better off continuing to charter and sail in clubs.

I’ve written before that eventually I realized all boats are project boats (“What Exactly is a Project Boat Anyway?“). And even though living aboard has made it easier to work on projects, the project list hasn’t gotten any shorter. For every project finished, we discover one or two new ones.

[Note: I’ve added a Projects page to the site, listing most of the major and minor projects completed]

Haul-out in June 2015

Another reason I didn’t want a project boat was I understood that boats are expensive but not in the initial purchase cost – an old boat is only as much as two new cars, which many middle-class families have (and if you told them two cars are a luxury rather than a necessity, they would probably disagree). The real budget killer is in the carrying costs – yearly moorage and maintenance.

In 3 years, we’ve spent 70% of the purchase price of the boat on projects – maintenance, parts, haul-outs and a small amount of labor. Since we’ve done almost all project work ourselves, only a small amount of spending was on hired labor – which is usually around $100/hour in the marine industry.

Counting moorage, we’ve spent 100% of the purchase price in three years. Of course, we expect project costs to go down in future years now that we’re done with a lot of the big stuff. The “big stuff” – two haul-outs, a transmission rebuild, and a rerig – account for 50% of total project costs. But maintenance on a boat never really ends, and those who think boats are expensive due to initial purchase price are probably either buying new (or newish) boats, or are bad accountants (not tracking all their maintenance/upgrade costs).

Interestingly, although we’ve only hired out about 30-40 hours of labor, those account for almost 20% of total costs. We’ve done over 2000 hours of labor ourselves. Doubling the hired hours (because they’re probably twice as efficient), that’s still only 4% of total labor hours making up 20% of costs. That goes to show if we had hired say 50% of all projects we could’ve spent 200-300% of boat purchase price by now.

Rerig in January 2017

What is a Refit?

So I think it’s fair to say we’ve completed a refit. Some major projects (rerig, resealed rudder, steering system rebuild, new electronics, solar, etc) plus countless smaller projects.

But what is a refit really? Yacht listings often boast that the boat had a refit, but that word is meaningless without defining what was done. It’s like remodeling a house – if they just painted the walls and updated the curtains, that’s very different from someone who added an extension, upgraded all the kitchen appliances, replaced the house wiring, re-roofed and redid floors.

As with the term “project boat”, refit is a continuum of different degrees. I take it to mean a significant amount of money was spent updating an old boat to meet modern boat standards. Of course, whose standards? That’s why it’s somewhat useless to use the term “refit” and better to define what projects were done.

Our Model for Project Work

On the other hand, our boat was not a project boat in the extreme way I envisioned that term. It didn’t sit in a yard for 2-3 years, and it was cruise ready the moment we bought it. So perhaps the spectrum of project boats can be put into two categories: boats that are ready to go, while doing some work on them, and boats that are so far neglected that they’re unsafe or un-cruise-worthy.

Sailing on the Sound in March 2015.

We wanted to do a refit with none of the sailing downtime that sometimes involves. For some people, the model of decommissioning their boat to work on it continuously for a year or two works for them, but I never would have been able to live with that. To justify having a boat rather than chartering and club sailing, I felt we needed to be using the boat for sailing and cruising.

So the priority has always been to minimize decommissioned time.

Decommissioned time (when the boat isn’t sailable) can be for something as big as a haul-out to something as simple as having too much stuff strewn about to be able to stow it in a reasonable amount of time.

We employ a few strategies:

- Divide and Conquer. A classic engineering strategy, this means dividing a project into smaller subtasks and doing one at a time (sometimes they can be parallelized too). The reason this helps reduce decommissioning is often you don’t need to complete 100% of a project before sailing. There may be 5-10 parts to it but only the 1 or 2 in the middle require temporarily forgoing sailing.

- Clean as you go. If you have tools strewn about, paint cans, trays of mineral spirits, etc, it’s going to be a lot harder to stow all that stuff to go sailing. So at every subtask we clean up things we won’t need for the next task. No longer need that hammer? Put it away. Done painting? Clean up the brushes, drop cloths, paint cans.

- Sailing comes first – sailing is #1. All projects get planned around sailing. If a planned sail is interfering with a project, the project can wait.

This also means we sacrifice project efficiency for sailing uptime. For example when we get around to replacing our acrylic port windows, we’ll do one at a time rather than removing all 4 at once.

Timing of Project Work

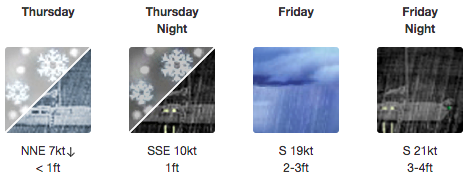

This does require some careful planning however. The peak of the PNW sailing season is only 3-4 months long, so to get in significant long cruises requires finishing all the project work well before the summer. So every year we do most of our project work in the winter and spring. Most other PNW cruisers seem to have figured this out too, but some still wait till summer, when all the marine service providers are swamped with long waitlists.

Each year we’ve actually been shifting our project time earlier and earlier – now it really ramps up in November and we aim to get the big stuff done by February or March. We learned that aiming to wrap things up in May or June is foolish because boat projects always take longer than you think – plus we’re busy with other things like provisioning for our summer cruise, making arrangements for mail, our car, work, etc. And, if any of the projects require assistance from a professional, most of those popular people are already swamped by April.

Typical winter working conditions.

In Conclusion

In retrospect, in the boat buying process I had no clue how much work a refit can be, or what constituted a project boat, or what our standards would be for a boat. This is something you really just need to learn through experience.

But, I learned I actually like boat projects, at least most of them. So even though we basically finished the “refit” 6 months ago, having finished all the essential safety projects, I’ll still continue doing projects for as long as we have the boat. After all, it’s a boat – the projects never end!

Patrick,

I love the part about doing one window at a time to minimize downtime. I couldn’t agree more. If you have a boat, your priority better be to get out and use it otherwise your price per adventure really goes up. PS – love the blog!

Jason

I feel like its never ending on my boat. Nothing major but every year there are certain projects to be done to keep on top of it. But even so I do love it. I just try not to add up all the $$ i spend!

Great post. I think most folks are in the same boat as you in that it’s never ending. In my mind, we’re always “refitting” Yahtzee. We work on projects continuously while throwing in some larger scale jobs when they pop up or when we have time and money to get them done. A true “refit” is for those that have a lot of money to plunk down all at once on a bunch of gear and work.

I think that’s the right way of looking at it. A “continuous refit” is the best way to maintain an older boat while still getting benefits (lots of sailing) out of it.