Here’s some more GoPro footage from the Van Isle trip, heading back east in the Strait of Juan de Fuca from Port Renfrew to Becher Bay.

Be sure to watch in 1080p HD if you’re on a fast connection.

Here’s some more GoPro footage from the Van Isle trip, heading back east in the Strait of Juan de Fuca from Port Renfrew to Becher Bay.

Be sure to watch in 1080p HD if you’re on a fast connection.

For over a year now I’ve had the dream of sailing down to Mexico, cruising the Sea of Cortez for a while, then sailing out into the Pacific to Hawaii and then back to Seattle. Living the adventure everyone talks about.

It was an ambitious goal, born from a desire for freedom, adventure, and breaking out of the standard pattern of life – one of working oneself into the grave. We work and work all our life, and for what? To buy a bigger house and fill it with more possessions that we hardly ever use? To have more money in retirement to spend in the bingo hall?

World cruising had all the attributes of the perfect escape from normalcy – adventure, vagabonding on the cheap, and a connection with a simpler natural world where burying your nose in your phone as you walk around isn’t the norm.

I read all the cruising books. “The Voyager’s Handbook“ by Beth Leonard was my bible. Capn Fatty Goodlander, and Joshua Slocum’s “Sailing Around the World Alone”. Larry and Lin Pardey’s “Storm Tactics.” All of these books made cruising sound simply awesome! Sailing seemed like the perfect way to travel the world – cheaper than a hotel room, and you get to bring your stuff with you too (rather than just what you can fit in a backpack).

I thought ocean sailing would be an adventure – big long rolling waves, steady consistent winds, beautiful ocean expanses, and peaceful nights under a blanket of stars. That’s not what I found. During our 2 weeks on the west coast of Vancouver Island we had two days of zero wind in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, requiring many hours of motoring, short and steep cross waves off the coast of Van Isle, and winds that were anything but consistent (lasting usually just 1pm – 6pm, and either not enough – less than 5 knots – or a bit too much – greater than 25 knots).

The ocean for most of 2 weeks was a somber gray expanse, with gray featureless clouds right down to the horizon, looking exactly the same in almost every direction. The star filled nights I had hoped for were missing 12 days out of 14, since cloud cover usually blocked out the sky.

And sailing long distances was exhausting – even just 25 miles left us dead tired and spent for the day. We hand steered most of the time because the wheel autopilot isn’t strong enough to handle 5 foot waves coming from all different directions – a wave from the port quarter would push us starboard followed by a wave from starboard later pushing us to port, requiring strong, quick ¼ turns of the wheel to keep us on course.

Yes, it’s true we were really still doing coastal sailing – coastal sailing that just happened to be in the ocean, but not true ocean sailing with no land in sight. And the land – with its shallows, points and currents – was what caused the cross waves and wind changes oftentimes. And the fields of crab pots to dodge.

But I realized the ocean 100 miles offshore wouldn’t be any easier. And the mechanical problems we had this trip (When You Motor Can’t Go Forward, Drive in Reverse, Engine Problems in the Strait of Juan de Fuca) made me realize how quickly it could get miserable if the engine failed ten days out from shore.

The saying goes amongst cruisers that cruising is “fixing your boat in exotic places.” But this started to sound like a mere coping mechanism for a sucky situation – I didn’t want to be fixing the boat in exotic places. I’d much rather be fixing it at home, safely on dock and within access of Internet references. Replacing fuel filters and bleeding the engine at anchor in Neah Bay was not fun, and it’s quite a stretch to even begin to consider Neah Bay an exotic location.

I began to think long distance cruisers just have really bad memories – they forget the bad parts so quickly that they’ve erased the trials and tribulations of offshore voyaging by the time they’re due to do it again.

But the #1 reason I realized long distance sailing might not be for me was due to how often it actually consisted of motoring!

Motoring a sailboat really kills me – call me a traditionalist, but motoring a sailboat makes me imagine the boat crying tiny tears of sorrow into the ocean. Sailboats are beautiful, amazing works of engineering, and it’s truly a privilege to own one. Burning diesel is not what sailboats were meant to do.

We’re not ones to shy away from sailing in light wind. We’re good at trimming for light air, have a boat that sails well in light air, and often we’ll be sailing in 5 knots of wind while most of the other sailboats around us are motoring someplace. But at the same time we’re not impractical motor-hating tyrants – we aren’t going to sail 4 hours at 1 knot. Covering 4 miles in half a normal work day is just really frustrating.

Cruising long distances pretty much requires motoring long distances. I thought the ocean would have at least some wind most of the time, or at least in the afternoon. But that’s not the case. We motored for 8 hours between Bamfield and Port Renfrew, crossing the western Strait of Juan de Fuca around 2pm over glassy calm waters. Neah Bay buoy was reading 2 kts I believe. We motored out the Strait of Juan de Fuca for two days as well, with no wind for most of each day. The 2nd day we had enough wind in only the last hour (4-5pm) to sail into Ucluelet.

This is not just a Northwest phenomenon. A survey of other cruisers in the Puget Sound Cruising Club who had cruised around the Pacific Ocean said they motored 50 to 85% of the time (it varied between couples). Motoring for over 24 hours is not uncommon.

The one beacon of hope I saw in this disappointing awakening was the realization that you don’t have to be a motoring sailor. Who decided you had to go 50 miles today? You did. When you decided to make a passage that has no safe anchorages for 50 miles. Or when you decided to run ahead of a storm. We get to choose whether we are motoring sailors or sailing sailors.

And the best way to avoid having your sailboat be a slow motorboat is to keep your passages short – really short, like 20 miles. That way if the day has 8 kts wind from 2-4pm and calm wind the rest of the day, you can wait for the wind and do some light air sailing and get to your destination in 3 or 4 hours. If you were trying to cover 50 miles with no motoring, 2 hours of 8 kt wind simply wouldn’t do it.

And this is the sad, roundabout way I came to the conclusion that the best way to avoid my #1 problem with long distance cruising was to not do long distance cruising.

It’s heartbreaking having to dismantle a dream. Especially a dream you’ve spent years building up in your mind. It took years to build up and mere days to realize it might not really be what I want.

Deciding not to cross oceans feels like a defeat. Like I’m wimping out because it’s scary. The truth is it is scary, but also not as fun as the books I read made it sound. When people write books about cruising they don’t write in detail about all the bad parts or boring parts. That’s not what sells books. Cruising bloggers don’t usually write about the long boring passages they had motoring either. They just show the amazing photos of fish swimming in coral reefs from when they got there.

Now I’m learning to read between the lines. Laura Dekker’s book is one of the more honest ones I’ve read. She mentions the times she was becalmed, sometimes for days at a time, the hours spent motoring with one of the two diesel engines onboard, the big waves and cross waves that tossed her boat around making life rather uncomfortable, and the birds that turned the boat into a carpet of bird poop.

A couple months ago if I read someone else writing the very words I’m writing now, I’d be silently judging and thinking of all the reasons they couldn’t hack it because they weren’t prepared enough, or experienced enough. Now I realize if you haven’t been in the ocean you really have no idea of knowing whether you’d like it or not. I can still change my mind. Maybe I could go offshore, and could prepare the boat for it – but maybe I don’t want to.

I do know it’s very easy to feel brave when sitting at a computer in the safety and comfort of home reading CruisersForum. It’s entirely different actually being out there in a tough situation, alone and cut off from any outside assistance.

But at least I have clarity now – I like cruising sounds, not oceans. Comfortable sailing on relatively smooth water in 10 – 25 knots of wind, with great anchorages every 10 to 20 miles so we can sail all afternoon without motoring and then drop the anchor for happy hour beers and snacks.

There’s plenty of fun to be had in Puget Sound and the Inner Passage, and more than enough adventure to last a while.

We were ghosting into the entrance to Matilda Inlet, before the point blocked the remainder of a 5 knot breeze. Fingers of wispy clouds intertwined with the dense evergreen shore. As we lost all wind, a light rain started.

We motored about a mile south, past the tiny town of Ahousat, into the right (west) fork of the inlet. There were no other boats there. We dropped anchor in about 15 feet, the anchor setting easily – a welcome luxury after recent deeper anchorages (we don’t have a powered windlass and it’s a lot of work pulling up 100+ feet of chain later).

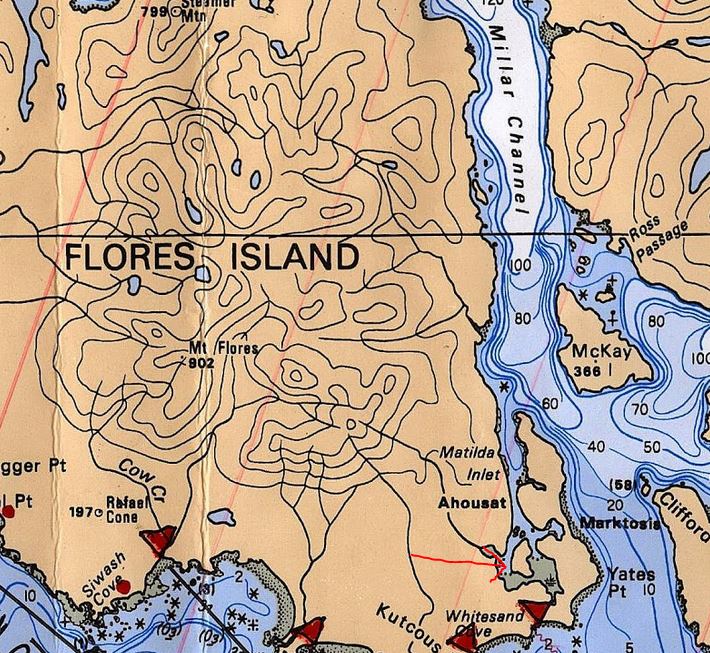

Matilda Inlet in the lower right – we anchored in the left fork where I drew a red arrow.

(Note chart not intended for navigation)

After turning off the engine, Natalie said “Do you hear that?”

“What?” I said. “I don’t hear anything.”

“Exactly,” she said. “It’s silent here.”

And it was. We had only the sounds of nature – a couple birds chirping, a slight breeze blowing through the trees.

It seems a silly thing to find notable, but most anchorages we’re used to aren’t that silent – with 4 or 5 other boats present (or 15+ for the big ones), you hear voices, generators, loose lines slapping against rigging, etc.

Matilda Inlet had a magical feel to us. An anchorage so perfect it felt like we had discovered a secret paradise. It’s completely protected inside a mile long inlet, surrounded by lush evergreen forest, and a family of four eagles kept us company soaring majestically over our heads. A man-made bathing pool on the shore is a short dinghy ride away. A rainforest-like hiking trail leads to a beach where you can find a sea cave.

The man-made pool at Matilda Inlet

We liked it so much we stayed a second night. The first night we shared the anchorage with one other sailboat, and the second night had it all to ourselves.

If we had to pick one reason it was worth going to Clayoquot Sound, it’d have to be the empty anchorages. Heelboom Bay was another one we had all to ourselves. Of 6 nights at anchor in Clayoquot, two nights we were alone and three nights we had only one other boat present. Only one anchorage had more than one boat besides ours (Hot Springs Cove).

There’s something really special about having an anchorage all to yourself. It’s a true feeling of seclusion, peace and quiet, and oneness with nature.

Heelboom Bay had the most spectacular sunset of the trip. As the evening progressed, the sunset just got better and better. At 9pm I was thinking “this is a pretty good sunset.” By 9:30 I was thinking “wow, this is the best sunset I’ve ever seen!”

The sunset was reflecting off clouds onto the water in almost a 180 degree arc, with our view out the bay open to the east – looking upon the mountain ranges of Vancouver Island.

Check out my GoPro video on YouTube (turn on HD quality if you’re on decent Internet), which also includes footage from our sail to Bamfield the following week:

This might have been the first time I knew real fear. We were having engine problems in the Strait of Juan de Fuca in 4 foot ocean rollers and no wind. Our engine power was dropping randomly, and at this point I had no clue why.

I’m not a person who frightens easily. Rock climbing, mountaineering, auto racing on a track, roller coasters – those things I would hardly even call scary. The only two things I’ve ever really found scary were skydiving and spelunking (caving, but in a random cave in PA where we crawled through tiny shoulder-width passages and the fear of getting trapped was very real).

But with our engine acting up in the Strait and no wind to sail, I began to realize how truly on our own we were. There was no easy rescue. If our engine completely failed we’d be stuck doing 360’s in ocean waves getting seasick for maybe hours before we could get Vessel Assist or a Coast Guard tow.

If you’ve never been out the Strait of Juan de Fuca before, the first thing you need to know about it is that it’s much bigger and more remote than you probably realize. In the whole day we hadn’t seen any other sailboats until the last hour, and there aren’t many safe anchorages you can pull into if something goes wrong.

Our lives weren’t in any danger. This wasn’t a real crisis compared to the life or death situations some sailors have been through. Yet it was still scary.

With time to think, and a quick check of the engine troubleshooting table in the Don Casey book, it was pretty clear it was probably a clogged fuel filter. But, I couldn’t help worry about all the other things it could maybe be – what if this was some weird, hard to fix issue rather than the fuel filter? What if the engine was actually overheating and our temperature alarm was broken? What if the fuel lift pump was broken? An air leak in the fuel lines? Would we continue on to the outside of Vancouver Island only to find the engine failing again in an even more remote location?

We shut down the engine and I did an inspection. With the lack of wind and the 4’ rollers, the boat quickly turned beam to the waves, which made below decks work fairly seasickness inducing.

I really didn’t want to try changing the fuel filter at sea. We restarted the engine, and were able to get it to run fine at a low cruising rpm (1800-1900). We slowly motored the last hour into Neah Bay.

Maybe it was our engine problems, or the gray chilly weather, but we found Neah Bay very glum and depressing

As I motored towards a dilapidated-looking unattended fuel dock, the engine died. Bad timing. Restart engine, died again. Ugh! Okay, what now? We’re 100 feet from the fuel dock, in 15 knots of wind (blowing off dock/land fortunately), gray overcast skies with a gloomy early darkness approaching.

We quickly raise the main halfway, and decide to sail onto anchor. That works surprisingly well. The most stressful part was making sure we got the anchor well set on the first try, since I didn’t want to have to do it all over again. Plus we only had the wind to set / test the anchor, and I didn’t want us blowing onto the rock jetty across the harbor in the middle of the night.

We had 15-20 knot winds in the anchorage all night, which coupled with worrying about the engine and the anchor holding, made for a restless night.

Fortunately the primary fuel filter (a Racor) was the problem, and replacing it with one of the two spares I had fixed the issue. But I was still paranoid maybe that wasn’t truly the cause, or maybe there was another secondary problem. I replaced the Yanmar fuel filter (on engine) too just in case.

In a way I felt stupid worrying so much about a fuel filter clog. Fuel filter clogs are mundane, routine stuff for people who cruise in Mexico and other areas with dirty fuel. But this was the first time Violet Hour had really let us down (in reality it was Yamagachi, the name we gave our engine, who let us down). And I had realized how truly dependent we were on engine power when in a strait with no wind.

The fun wasn’t over yet though – the secondary filter (on the Yanmar) leaked fuel for the next four days. So I was mopping up diesel from the bilge and under floor panels every evening.

Yeah, this first week was pretty tough.

The Yanmar fuel filter has a metal collar with slightly raised nubs and screws on to attach the filter housing. Fuel was slowly leaking from here whenever the engine was on. I tried tightening it as much as possible by hand, and eventually with a ViseGrip wrench (that was the only thing I could get a decent grip on it with). That still didn’t fix it. Eventually I tried replacing the rubber gasket inside the housing, even though it looked fine, with a spare I had onboard (fortunately). That worked!

Marinating chicken in the cockpit since the swell in the Strait was too rolly to work below.

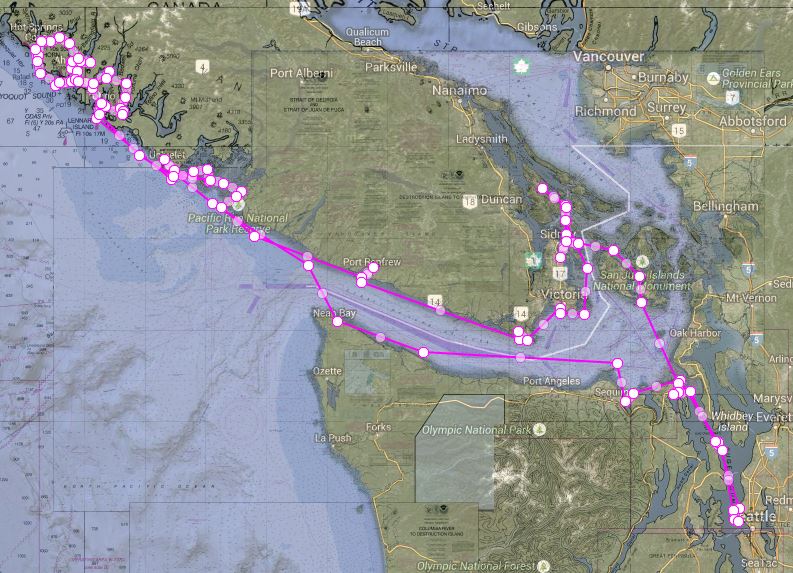

Last week we got back from our 4-week trip out the Strait of Juan de Fuca, up the west coast of Vancouver Island to Barkley and Clayoquot Sounds, back through the Strait to Victoria, around the Gulf Islands a couple days, and then back to Seattle.

This was about 600 nautical miles, but that’s just the straight line distance – with tacking and jibing when we were sailing, we probably did closer to 800.

Overall route (not all circles represent stops, those are just the points where I needed to change the route line direction)

Detailed route of Barkley and Clayoquot Sounds.

As cruisers often say, the highs were very high and the lows very low. Cruising is often more intense, in both the good and the bad, than land life. Our two biggest problems were mechanical – the fuel filter clogging in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the transmission progressively failing. There were human challenges too – dealing with very tiring passages, mild seasickness, difficulties in confused ocean waves, challenges controlling the sails in high winds, and almost swinging into rocks at anchor.

Despite the challenges, I feel we did quite well. We didn’t have any failures of seamanship – no groundings, no navigational mistakes, no anchor dragging, no poor timing of weather, no docking mishaps.

There were hard times, but for this post I want to focus on the fun times – all the amazing experiences and especially the great photos I got.

Stream-fed bathing pool at Matilda Inlet

Anchored in Matilda Inlet (our favorite anchorage of the trip)

Wildlife

The trip was not a roadside safari, yet we saw plenty of wildlife.

Great Hikes

Portland Island

The sea cave at Effingham Island

Hiking to the hot springs

Arrived in Victoria and docked in front of the Empress Hotel

Our last day – with a failing transmission but a 12 knot wind at our backs, I pointed the bow pointed at Mount Rainier and we sailed home.

There we were in the Gulf Islands, drifting between Sidney Spit and several threatening rocks on flat, windless water. We were motoring backwards with our mainsail up. Other boats must have thought we were completely crazy. While sailboats around us were motoring like normal, we were traveling in reverse.

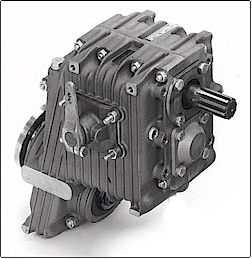

Our transmission was failing – the forward gear would no longer engage. But reverse worked just fine – meaning we could motor in reverse, but in forward could only go about ½ a knot – the speed gained from the prop spinning at about 500 rpm with the clutch slipping; and that would only work in windless, waveless conditions.

A failing transmission was a giant kink in our plans – everything became more difficult. Getting into marinas without forward power was scary, so we avoided marinas except for one stop in Ganges to get a mechanic to check out the transmission. Sailboats don’t drive well in reverse (the rudder isn’t designed to work that way), but we could motor that way at 2-3 knots a short while if we needed to get out of trouble or to some wind.

Luckily sailboats have two means of propulsion – the engine, and the sails. So we took light air sailing to new levels – sailing in 2 knot winds where every other sailboat was motoring. There are a few sailboats that sail across oceans with no engine, but those sailors are by far a tiny, minuscule minority. I don’t know how they do it, and have tremendous respect for someone who could. Sailing without a motor is an exercise in frustration when wind can be absent for hours, or days, at a time.

Fortunately the transmission magically popped into forward after 2 ½ hours waiting, and we slammed it into full power for 10 hours from the Gulf Islands to Port Townsend, crossing a glassy, windless Haro Strait and a windless eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca. We had to exit Cattle Pass against current, but with the motor finally in gear there was no way we were turning it off – if we throttled down too much the clutch could slip and we’d lose forward gear again.

This was like our own version of the 90’s movie ‘Speed’ where they’re on a speeding bus that they can’t slow down.

A dead transmission is not a problem we could fix underway. No one I’ve heard of carries spare transmission parts with them, and repairing it requires removing the transmission from the prop shaft – this model, a Hurth v-drive, is not easily opened up.

And we don’t know what caused it – as far as I know, we didn’t do anything wrong that would contribute to the transmission issue. The mechanics we’ve talked to so far thought most likely it was just old and gradually wearing out.

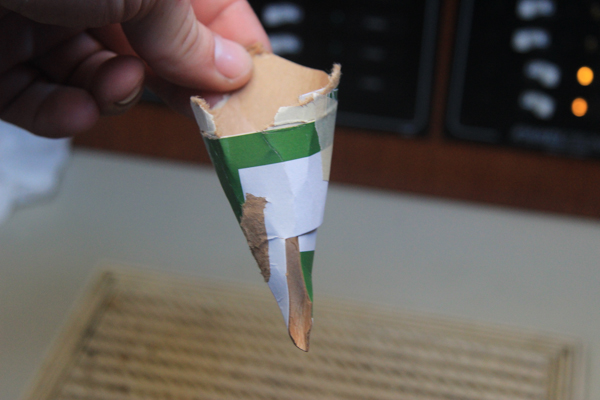

A makeshift oil funnel I made out of a beer box because the engine oil funnels I had were too big to fit the transmission. The oil looked okay, but I topped it up since we didn’t have any other ideas.

Perhaps what scared me even more than whether or not we’d be able to get home was that this could have happened anywhere. If we decided to sail to Mexico someday, this could’ve happened 50 miles offshore of the Oregon coast. Then we’d be in ocean waves (possibly with no wind) and no power. We’d be far from rescue, and far from any ports that could repair the issue. And there’d be nothing we could do to fix the problem ourselves – unlike most other boats problems where we could have jury rigged a solution.

Even if the transmission had kicked the bucket when we were on the west coast of Vancouver Island we would’ve been pretty screwed. There are no major marine ports like Port Townsend there, probably few if any mechanics experienced in marine transmissions, and the boat would’ve been stuck there for months while we tried to fly parts in.

After anchoring overnight at Port Townsend, we sailed all the way back to Seattle the next day, having a wonderful downwind sail with blessedly consistent 10-12 knot winds. Then came our last challenge – getting into Elliott Bay Marina without forward gear and a 12 knot wind blowing through the entrances! We could sail in, but sailing a 38 foot, 18,000 pound displacement boat into a marina you’ve never entered before is not so easy, nor necessarily a good idea when there are breakwater rocks and million dollar powerboats. After an hour of getting pushed by wind and current, when we were just about to try reversing in, the clutch miraculously engaged in forward and we made it in!

Violet Hour is out of commission now for at least a month, all of August which is prime sailing season in Seattle. And will cost many boat bucks to repair. So this is a disappointing end to our trip, but there were many great moments before this – more to come soon!