As we began to motor out Hakai Pass at 5 am, I could see the swell would be getting pretty sloppy soon. But I had no idea how bad it would get. An ebb current was meeting a 2 meter (6 foot) westerly swell and W 15 of wind, creating monstrously uncomfortable waves. Both Natalie and I were nearly instantly seasick, despite taking Sturgeron upon waking (4:30am).

The waves were 6 to 9 feet, very closed spaced and cresting in foaming white water. Heading into the opposing steep swell was nearly stopping our boat at times, despite our Yanmar churning away at 2300 rpm. Our speed was reduced to 2-3 knots at times. The wind was precisely on the nose, and we hadn’t yet cleared dangerous rocks to our port, which the swell was trying to push us towards.

As we crested a wave, sometimes the bow would pound down into the trough, and at times we nearly buried the bow. We were rolling and pitching in the confused swell, with barely enough power to get over the steep waves. It was difficult to even stand – I was braced behind the wheel, unable to sit because the bucking and rolling would throw me across the boat. We could do this for a while, but 70 miles of it (~14 hours) was pretty hard to imagine.

We decided to turn around. It was the right decision, but completely demoralizing because we had staked a lot on this plan and spent 6 days of anticipation waiting for a weather window. But it was the wrong forecast, wrong swell, wrong wind, and probably even the wrong course / plan to begin with.

Then we started taking on water – the bilge pump turned on and we saw water streaming out the side. I checked the bilge and found 5-10 gallons filling the keel sump, which we normally keep pretty much dry at all times. That’s a lot of water to take on in only 30-60 minutes. But not enough to be a major thruhull breach.

While sailing back into Hakai Pass I checked everything and couldn’t find any active leaks. Later I figured out our PYI dripless shaft seal had probably been spraying water all over the engine compartment. The steep, powerful seas were shoving us around so much that apparently they were pushing our prop / engine enough that the shaft seal wasn’t holding tight.

Later inspection found the shaft seal collar (donut) had actually slipped about 1/4” on the prop shaft. Fortunately I have a backup retaining collar forward of that (which the PYI collar was now abutted against). Having compression on the bellows is critical to prevent the shaft seal flooding the boat.

We retreated and regrouped in Goldstream Harbor – ie, took a nap, because we were both exhausted after having barely slept (Adams Anchorage was really rolly!).

Doubts ran through my head – why couldn’t we handle this when other people seemingly can? R2AK and Van Isle 360 both do stuff like this (or much crazier). But just because it’s possible doesn’t mean it’s fun, and we’re out cruising to have fun. It was a tough reminder that the sea is powerful. There’s a good reason the saying goes “fair winds and following seas.” We had neither.

The Original Plan

We’ve been cruising the Central Coast for a while and wanted to move on to the west coast of Vancouver Island. Leaving from the north end of Calvert Island and crossing Queen Charlotte Sound seemed sensible, because it would give us a good sailing angle to the typically NW wind.

We did a lot of planning for this passage because it has the potential to be pretty rough. It crosses through three forecast regions – Central Coast, Queen Charlotte Sound, and the northwest coast of Vancouver Island. Queen Charlotte Sound and the west coast receive ocean swell, interacting with the wind waves and land features.

It’d be about 70 nautical miles and in our planning we estimate an average speed of 5 knots (to conservatively account for non-ideal conditions and the fact sailing rarely follows the straightline rhumbline), which would mean about 14 hours. Doable in daylight, from about 4:30am – 6:30pm, giving us about 3 hours extra before sunset in case of unexpected delay. Aiming for Sea Otter Cove, we would definitely not want to do a night entry because it’s a very shallow anchorage, reached through a narrow, rock strewn entrance.

The Weather

But as soon as we were ready to embark, the weather pattern switched against us – over the next six days, instead of NW wind, we had a southerly, a light day, a strong westerly, a light westerly. A westerly in Queen Charlotte Sound is problematic because it would mean holding to a perfect close hauled upwind course for 55 miles and going against a building westerly swell.

This June the North Pacific high has been struggling to move north. The position of the North Pacific high determines the direction and strength of wind, and brings the northwest winds and sunny skies we typically get in late June and July. Last year this started around June 15 in northern BC, but this year the high has been hanging out further south, along the California and Washington coasts.

Testing Our Patience – Waiting for the Right Weather Window

Waiting for a weather window has to be one of the hardest things we do in cruising. You wouldn’t think so, but it can be a trying test of patience and psychological will power. The weather doesn’t run on a schedule, and can easily stay adverse for 5 days or more. And each day as we sit at anchor, waiting to see if it will turn in our favor, our fresh groceries run lower and our water tank starts to deplete.

For most sails in protected waters we rarely need to wait more than a day or two. But for longer passages through open waters (exposed to ocean swell mixed with currents and headland effects) we need to be more cautious. It’s a fine line between a fun sail and a miserable sail or a long motor (which is almost as miserable).

We’re getting better at having patience though. Last year we got impatient leaving Haida Gwaii and it resulted in a terrible sail in a gale – but waiting for the right window would’ve meant 5 more days sitting at anchor with dwindling groceries and little to do (no shore access).

The New Plan

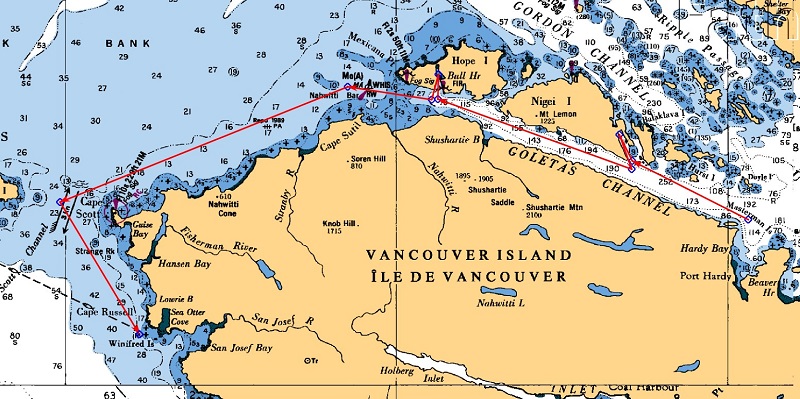

After we aborted our original plan at Hakai Pass, we decided to go back down the coast the conventional way – via Cape Caution and then to Port Hardy (since we were running low on groceries and water by now). And then we would reattempt Cape Scott via the conventional route.

Sailing around Cape Caution. Confused swell, but it was a good sail.

Typically people go via the Goletas Channel, over the Nahwitti Bar, and then west over the top of Vancouver Island. The Goletas Channel runs NW from Port Hardy and ends in the notorious Nahwitti Bar (which we would’ve avoided by sailing across Q Sound). The bar requires careful timing to cross at slack (and ideally with a low swell and low wind) – otherwise strong ebb currents running into a westerly swell on a bar with depths of only 30-40’ can create miserable (and potentially dangerous) waves.

The Slow Road to Cape Scott

After aborting at Hakai Pass it took us 5 days to get to Bull Harbor: Fury Cove > Clam Cove > Port Hardy > Port Alexander > Bull Harbor. Our sail to Clam Cove was one of our best Cape Caution roundings ever – we had to motor out of Fitz Hugh Sound, as seems common, but after that sailed in NW 15-20 the whole way, in not-awful 5-6 foot swell.

Going upwind in Goletas Channel can be surprisingly choppy – even with only NW 15-18 kts of wind, aligned with current, a very close spaced 2 foot chop forms. The prior day, on our way into Hardy Bay with 25 kts, Goletas looked a lot rougher.

At Bull Harbor we waited another day (2 nights) for a weather window. So counting the 6 days we waited on the Central Coast, it will have taken us 12 days to get to Cape Scott. Surely that must be a record for slowest ever!

But we don’t mind, because we’re having fun along the way, visiting anchorages we haven’t been to before, and focusing on maximizing sailing over motoring. Having freedom of time takes some getting used to. We’re so accustomed in life to taking the shortest road, but sometimes the longer road is the right choice.

Consolation prize for having to take the slow road to Cape Scott: fried food is what we crave when we’ve been underway for almost 3 months (cooking all meals onboard except for 3 or 4)

Entering Clam Cove