Sailing, actually sailing (not motoring around everywhere in a sailboat), is unquestionably difficult in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. Winds aren’t consistent, narrow straits and channels mean a lot of tacking or gybing, strong currents cause the water to kick up into rough, sharp waves, and land effects plus weather systems cause the wind to vary greatly from one area to the next.

But in the past 3 years (primarily in BC) we figured out how to sail in these waters, doing about 70% of our miles under sail. We do this because it’s what we enjoy – sailing a sailboat just feels right, uses less fuel, it’s quieter, and makes us feel more connected with nature and wildlife. I talked more about the reasons and tactics in my 2018 article “Cruising the Pacific Northwest by Wind Power.“

But now that we’re in Alaska we’ve had to relearn how to sail here. Alaska has a reputation for being a place where most sailboats generally do no sailing at all – many people say they never even took the cover off their mainsail! That’s very sad since you might as well have a motorboat then – with more comfortable accommodations and less vestigial weight and cost (from the unused rigging and sails).

The good news is it’s definitely possible to sail a lot in southeast Alaska! It takes effort, just like the Inside Passage does, but a few things make it a bit more challenging:

- Rain – It rains a lot! Sailing rather than motoring means more time out in the rain, raising or stowing sails or winching after each tack. Motoring, one can huddle under the dodger or bimini.

- Cold – colder temperatures mean our hands freeze when line handling. We have good sailing gloves but nothing is perfect when handling soggy salty lines. And sailing requires handling lots of lines – motoring doesn’t.

- Longer distances between anchorages – on a light wind day, being able to stop after 10 or 20 miles gives you more time for slow sailing. In Alaska, good anchorages are often 30 miles apart. Occasionally only 10-15 miles apart, but distances between ports are also larger – and eventually most boats need groceries, water or fuel.

- Light wind – it’s true that many days there’s only relatively light wind – 5 to 10 kts. In a typical rainy pattern, frontal systems come through bringing 15-25 kts, but for a few days between fronts there might be only 0-15 kts.

- Complex wind shadowing and williwaw effects. Mountains here are bigger, and they have a big impact on the wind. On one end of a strait you can go from sailing downwind in 15 kts, to no wind in the middle, to 15 kts on the nose (upwind) at the other end. Outflow winds from glaciers and cold river valleys can blast one section of the water with 20+ kt winds while past that section there’s no wind.

Normally, we learn through observation – watching other sailboats around us. But that’s even more difficult in Southeast Alaska than it is on the Inside Passage through BC. In a month and a half here we haven’t seen a single sailboat sailing, and have only seen a handful of motoring sailboats (2-3) on the water. Motorboats outnumber sailboats by at least 5 to 1.

Some light wind rainy sailing, with a reef in the main because we know there’s an acceleration zone ahead (Young Bay) where it did indeed build to 25 gusting 30 knots.

SE AK Compared to BC

Gales haven’t been as common or problematic as we expected. On the BC coast we typically spend time hiding out from gales about once a week from April thru June (and sometimes in July too, as in 2019 on the west coast of Vancouver Island). So far in Southeast Alaska the more common problem has been too little wind rather than too much wind.

No wind days, or just local areas of no wind, can be common.

However we’re happy this has been the case because the bodies of water up here get rough very quickly, in surprisingly low levels of wind (ex, 15 kts). All of the straits and sounds have current, and some of them are very large, creating plenty of room for fetch to build and currents to oppose wind.

The inside waters of SE AK still get a lot of sub-gale winds in the 20-30 knot range though. It seems to alternate between nearly no wind (0-5 kts) and pretty tough conditions (20-25 kts in a complex strait with current).

While in BC there are a few large straits to watch out for (Strait of Georgia and Johnstone most notably), in Southeast Alaska, nearly every strait or sound has similar sizable fetch and current to the Strait of Georgia.

Tactics for Sailing in Alaska

Gradually we’re learning how to sail in southeast Alaska. Most days, at least in April and May, have had some wind. Some of the techniques that have worked:

- Weather models (accessed in PredictWind or Windy):

- ECMWF 9km or 50km is our go-to for best accuracy in BC and we continue to use it in AK.

- NAM (5km) model is available here (it’s US only) and seems to be even better than ECMWF in SE AK – it looks like the finer grained granularity of the 5k model is better able to understand the effects of mountain and valleys on the wind.

- Topographical maps (Google Maps or Google Earth) – looking at the elevation and shape of surrounding mountains helps a lot in understanding where the wind will come through and where it will be blocked.

- The same topography that can sometimes block wind can also sometimes aid our sailing. In SE AK there seems to be greater diversity in wind directions – because of inlet outflow winds and different shapes to the straits and valleys, winds from the east, northeast, southeast, and northwest are all fairly common. In BC most winds follow the straits and are either northwest or southeast derived (ex, in Johnstone the wind may be from the west because it’s following the strait, but it originated from a northwest wind and pressure gradient in Q Strait).

In SE AK, because we may have an east wind while sailing in a NW-SE oriented strait, that sometimes enables us to stay on a broad reach or close reach for a longer time, sailing closer to rhumbline and with fewer tacks/gybes. - Our full cockpit enclosure is essential in Alaska. In BC it was critical too but here it’s even more important for increasing how much you can sail because it helps with two of the biggest obstacles to sailing (cold and wet – getting blasted with freezing wind and sideways rain while sailing in an unprotected cockpit).

It’s counterintuitive because a cockpit enclosure actually decreases ease-of-access to winches and sail control lines but we’re convinced as long as you’re still willing to make the effort of unzipping a side panel to sail, cockpit enclosure = more sailing.

Outflow Winds and Inflow Winds

Sometimes the forecast models get things completely wrong, but we’ve learned in some cases it’s possible to “read between the lines” and figure out what will happen even in those cases. Outflow and inflow winds seem to be the hardest for the models (and NOAA) to forecast. Outflow/inflow winds are caused by land warming or cooling creating a pressure differential with the cold marine air. “Taku winds” near the Juneau area are an example of this (although they are actually much more complicated than outflow/inflow wind – there are actually academic whitepapers on this, which the NWS Juneau office was kind enough to send me when I inquired).

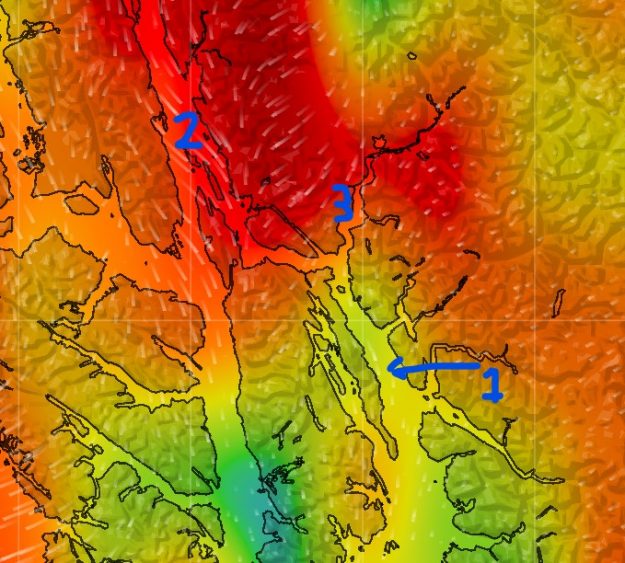

Here’s a situation where NOAA and models (ECMWF) predicted only N 10-15 but we got N 30 gusting with huge shifts in Stephens Passage, attempting to go from Tracy Arm to Taku anchorage:

- #1: Where we were (Stephens Passage, departing from Tracy Arm Entrance Cove).

- Model Forecast N 6-15, NOAA forecast N 15;

- Actual N 25-30 gusting 35.

- #2: Lynn Canal – Forecast 17-25.

- #3: Taku River inlet – Forecast 6-22.

In retrospect we can see that we should’ve interpreted the strong outflow from Taku Inlet and Lynn Canal as a warning sign of strong outflow winds which would easily flow all the way down to Stephens Passage.

Summary

Overall we’re probably sailing 50-60% of our miles here, a big reduction from our usual. This has been disappointing at times and probably the #1 thing we don’t like about cruising Alaska compared to BC. We’re using a bit more fuel, and having longer days whenever we move anchorages. However, 50% is still a lot better than zero.

A lot of the motoring comes from longer approaches into anchorages which are up inlets or channels with zero wind. Many anchorages have a 6-8 nautical mile approach (~1 hour motoring) through a windless bay, inlet or channel. The plus side is most anchorages we’ve been in have been very well protected.

There are also some ports where motoring 18 nautical miles in a narrow channel (Wrangell Narrows northbound to Petersburg) is the main way to get there.

Despite less sailing, there are lots of other rewards – amazing mountain views everywhere, and more wildlife and sea life than we’ve seen anywhere else.

I can appreciate your comments about the Taku winds. While in Juneau working, I was scheduled to return to Seattle and the Taku Winds blew so hard that flights were cancelled. I could watch the wind’s effects on the channel from my hotel and was very glad not to be in them.

Sounds like you have a greater-than-optimal reliance on good internet access though. Has that been a problem so far?

SE AK has pretty good cellular reception (consistent with what we had heard). Not as good as really populated areas like the San Juans but better than the North and Central coasts of BC. Most anchorages we’ve had some cellular in, sometimes only through use of our booster. I’m also reactivating our Iridium Go subscription because there are a few areas where there’s no cell or VHF weather.

Great article!

Coincidently, another blogger that I met in PT last season who had just come from the South Pacific posted an analysis of the South Pacific the other day: https://svcapri.com/2021/05/23/pacific-weather-patterns-why-the-pacific-doesnt-live-up-to-its-name/

In Stephens Passage, I’m curious – did you happen to look at the HRRR (especially the new sub-hourly version)? Being a mesoscale model that takes terrain into account, I wonder if it would have predicted the funneling effect better.

My experience in spending a lot of time in SE Alaska (different context) is that the weather can change violently fast this time of year – in the mountains at least. But you’re surrounded by mountains too.

Unfortunately no, I don’t have access to HRRR since LuckGrib isn’t available on Android or Windows.

You can request HRRR (and other) GRIBs through Saildocs for free: http://saildocs.com/gribmodels. There are a few free GRIB viewers out there if you don’t already have one.

Oh, I need to give that a try. Thanks!

SailDocs is the resource I always forget about. There is lots that it can do besides weather models. David Burch has blogged about it from time to time as well and has some good tips.

Send separate blank emails to: info@saildocs.com, gribinfo@saildocs.com, and gribmodels@saildocs.com and SailDocs will send you the list of commands for all it can do. You can even subscribe to regular updates of data at intervals automatically.